Eröffnung globale°-Festival / Kolloquiumsvortrag

19:00, Rathaus Bremen

David Safier (Bremen)

„Die Liebe sucht ein Zimmer“

Anmeldung bis 20.10

Conference: Coming to the Surface or Going Underground? Art Practices, Actors, and Lifestyles in the Soviet Union of the 1950s-1970s

Research Centre for East European Studies (FSO)

Registration until 07.11.2025

Wissenswertes

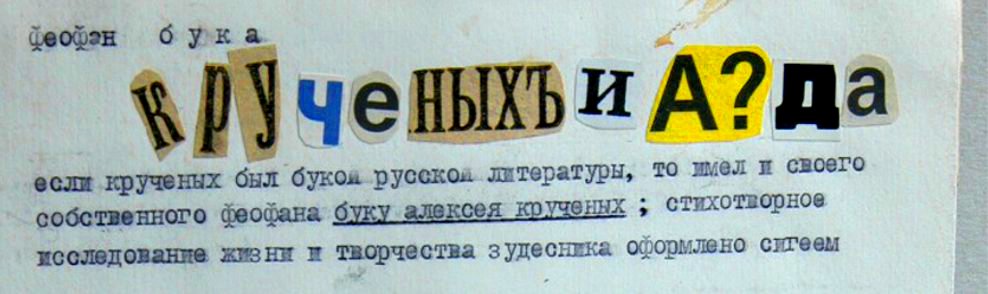

Czech Dream Book of 1988

A Letter from Karel Trinkewitz to Václav Havel. Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Prague Spring

Quelle: Archiv der Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, FSO 2-060, Karel Trinkewitz, Correspondence (with Václav Havel)

After writing about the dream in detail and trying to make sense of this strange constellation of images, Trinkewitz reminded his correspondent Havel of two books concerning dreams. One was Italian author Luigi Malerba’s “Diary of a Dreamer”, and the other was their fellow Czech writer Ludvík Vaculík’s “Český snář (Czech Dream book).” Both authors described their dreams on February 9th, 1979. Intriguingly, in both cases, the authors described scenes of violence caused by Russian officers in their dreams. Trinkewitz identified these two dreams with his latest one. It was, in his words, “a European dream” in criticizing Russian hegemony in Europe. The artist thought the region was largely threatened by the existence of Russia/the Soviet Union and that ordinary citizens’ lives were at stake. Trinkewitz asked Havel to tell Vaculík about his dream, which he thought of as his version of “Czech Dream book of 1988” and that resonated with the idea of a dream experimentally capturing fragments of contemporary memory.

Trinkewitz’ letter highlights the complexity of political consciousness combined with personal reflections around the late Communist period. The Prague Spring, in this context, appeared to have a long-standing psychological effect on the artist. However, what Trinkewitz anticipated—another Soviet invasion of Prague—did not occur. This was precisely thanks to those who did not give up the hope in the legacy of the protests of 1968—freedom of thought and expression, and the autonomy of Czechoslovakian society. One year after the letter was written, the country experienced a democratic transformation, and the artist even saw the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Lesetipps:

Klára Burianová: Karel Trinkewitz - O životě, Praha 2016.

Länder-Analysen

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

Discuss Data

Archiving, sharing and discussing research data on Eastern Europe, South Caucasus and Central AsiaOnline-Dossiers zu

» Erdgashandel

» Hier spricht das Archiv

» Russian street art against war

» Dissens in der UdSSR

» Duma-Debatten

» 20 Jahre Putin

» Protest in Russland

» Annexion der Krim

» sowjetischem Truppenabzug aus der DDR

» Mauerfall 1989